God Bless Annie Dillard

A middle-aged man aggressively picks his nose in broad daylight. He believes he is alone in the front seat of his car. Unfortunately for him, he is not as alone as he thinks. Parked next to him at the stoplight, I am spellbound by his digging. How many knuckles is that? As he completes the task and turns to dispose of the evidence, we lock eyes. Fight, Flight, or… we share a 2-second eternity before the green arrow graciously invites his departure. I apologize silently as he peels away. Above his shrinking tail lights is a bumper sticker; a cluster of blue turtles in the shape of a heart. My mind reaches to tie these two data points, nose-pickers and turtle-enthusiasts, but the lines fall short and slacken. Mystified, I pull away and enter the flow of traffic.

This is a bad habit of mine: the watching of strangers in their vehicles. A couple in a beat up Jeep full of stuff talk loudly and at the same time, arms flailing in unison as if they are miming each other. I can’t help myself. This is my version of reality TV. Fishbowls of private life sloshing down the public road, unaware or uncaring of my presence. It’s a bit sick, my furtive watching, and occasionally it will bite my butt, like with the turtle-picker, but life is short and full of sorrow. I allow myself the pleasure.

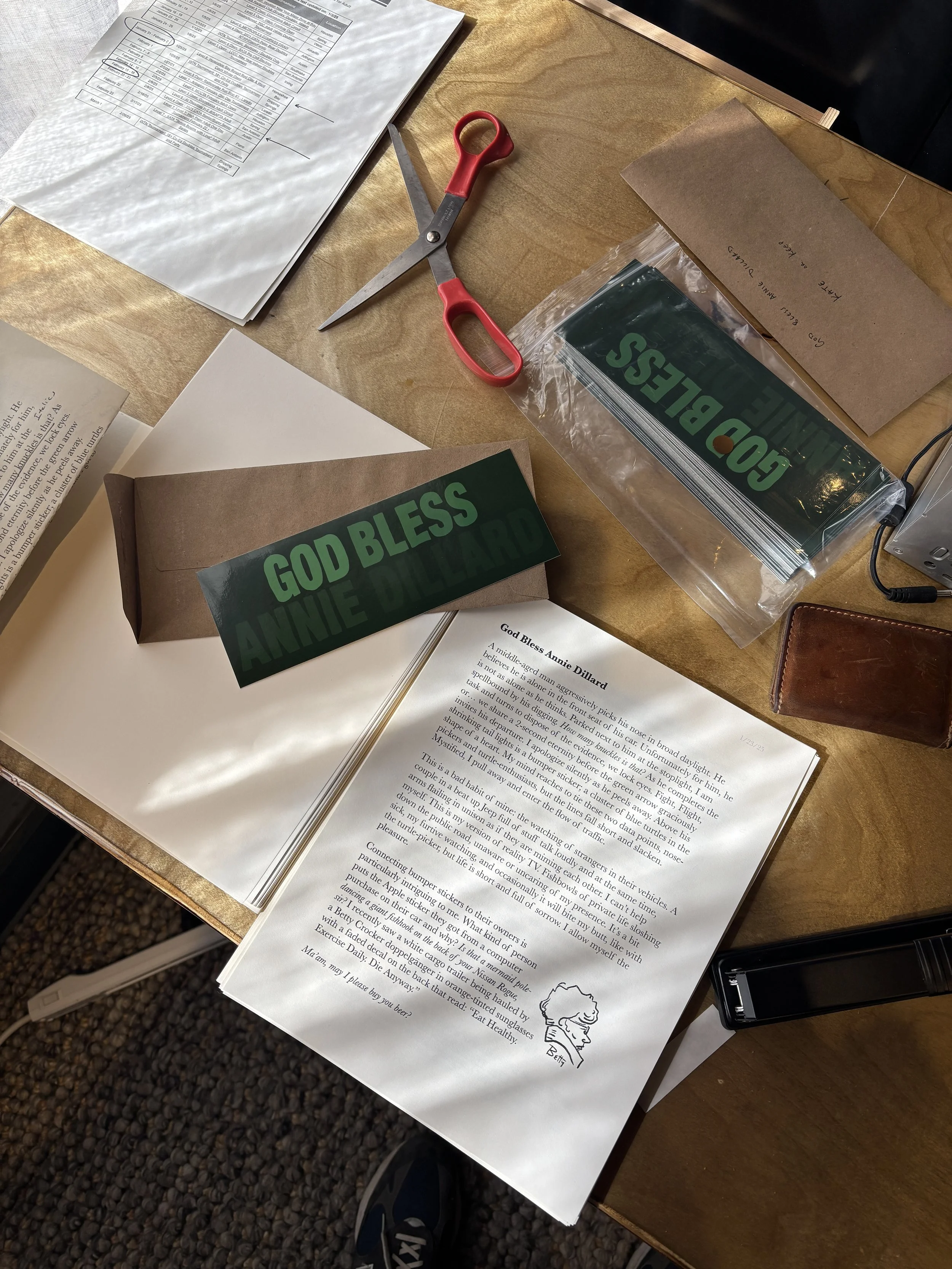

Connecting bumper stickers to their owners is particularly intriguing to me. What kind of person puts the Apple sticker they got from a computer purchase on their car and why? Is that a mermaid pole-dancing a giant fishhook on the back of your Nissan Rogue, sir? I recently saw a white cargo trailer being hauled by a Betty Crocker doppelgänger in orange-tinted sunglasses with a faded decal on the back that read: “Eat Healthy. Exercise Daily. Die Anyway.”

Ma’am, may I please buy you beer?

On the same trailer was another sticker, which I assume to be one of the most popular pieces of bumper art ever: GOD BLESS JOHNNY CASH in white text over a field of black befitting the man. And I got to thinking… Why Johnny Cash? Why God Bless Willie Nelson? What is it about these men that our response to their music would be to anoint them with our prayers? The story I tell myself, much like those I write about my fellow commuters, could be wildly mistaken but it goes like this. I think that by the time these stickers are being printed, a large swath of the population has fallen in love with these men. They are stars. At the same time, we know that our love for them hangs in the balance because their lifestyle and work put them in harm’s way. Like a tracker out in front of the regiment, great artists go off into the wilderness of the soul while we wait pensive for their return and guidance. I think we as a collective we can intuit that it must be pretty hard to be Johnny Cash. “God bless that man. He needs all the prayers he can get.” God only knows what goes on behind the eyes of a man who writes the lyric:

“The beast in me is caged by frail and fragile bars,

Restless by day and by night rants and rages at the stars”

Like June Carter Cash, we are powerless to fight the darkness within the man we love, so we do the only thing we can. We pray. Now I know I’m writing about Johnny Cash at some length here, but truth is, he isn’t one of my heroes. His flavor of darkness is not my own; however, he got me thinking about who I would put on that sticker. Who is a hero of mine who lives hard? Maybe not in the style of Willie or Cash, but who is someone who I follow, who ventures into the void to bring back news of road ahead?

Annie Dillard is one of those people for me.

Annie Dillard is the author of a bunch of books, 4 of which sit on my shelf: Holy the Firm, The Maytrees, The Writing Life and most famously, the 1974 Pulitzer Prize winner for non-fiction, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Written when Dillard was 29, the book chronicles her experience exploring a creek behind her home in all seasons and bearing witness to the enormity of life transpiring there. Her descriptions of the place are so evocative that upon first reading I thought: I must see this Tinker Creek with my own eyes! Surely, it is stunningly beautiful. And while Tinker Creek in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley is undoubtably pretty, it is not dissimilar to any number of wet places in my own backyard. It is Dillard’s accounting of the place that stuns. Read her report of a winter’s walk to the creek:

“Today is one of those excellent January partly-cloudies in which light chooses an unexpected part of the landscape to trick out in gilt, and then the shadow sweeps it away. You know you’re alive. You take huge steps, trying to feel the planet’s roundness arc between your feet.”

279 pages of this. Writing that is demanding, musical, rewarding, and human. But Dillard’s reckoning does not stop at observation. She then sifts her self through the screen of the creek, apprenticing to its craft and acolyting its message. She notices a butterfly flitting along with tattered wings and writes:

“I am a frayed and nibbled survivor in a fallen world, and I am getting along. I am aging and eaten and have done my share of eating too. I am not washed and beautiful, in control of a shining world in which everything fits, but instead am wandering awed about on a splintered wreck I've come to care for…”

It is a rare and beautiful thing to read a author who so completely disappears within her own writing. Yet Dillard is not done yet. Courageously, she details a personal encounter with the paranormal. Coming upon “the tree with the lights in it” as she puts it, she is set ablaze with what can only be described as divine revelation.

“One day I was walking along Tinker creek and thinking of nothing at all and I saw the tree with the lights in it. I saw the backyard cedar where the mourning doves roost charged and transfigured, each cell buzzing with flame. I stood on the grass with the lights in it, grass that was wholly fire, utterly focused and utterly dreamed. It was less like seeing than like being for the first time seen, knocked breathless by a powerful glance.”

It is an untidy moment and she lets herself be swept away. In the pages that follow, I fear the author may be coming unglued. Her complete lack of self-consciousness unnerves my ego deeply and I am left with far more questions than answers. Without meaning to, I find myself in prayer for Annie Dillard. This is truly hazardous terrain she walks: to be out in the open, so vulnerable, so attentive to the place that the ground itself can burn beneath her, or the cold creek carry her away. She needs all the help she can get. And yet this perilous setting is precisely where Annie Dillard returns to again and again, falling through the trapdoors of attention and vulnerability into depths of meaning.

God Bless Annie Dillard.

She goes first. She pays the price of her way of being: weeping when called to, despising the despicable, watching death’s parade, suffering loss, bearing its weight, affected by life. She pushes the boundaries of attention and vulnerability to show that their extremes are not fatal. Though it be far easier to stay behind walls, keep up appearances, or medicate away the unnamed pains, she invites the reader to seek their own “tree with the lights in it”, to open oneself to the possibility of being swept away.